Ever since I was a small child, I’ve loved fantasy stories. Recently, I started getting into older works of fantasy – A Princess of Mars and Lord of the Rings. Despite these stories having a reputation for being cliché, they came across as fresh and interesting. Why? Because up until that point, I had only been familiar with imitators of Edgar Rice Burroughs and J. R. R. Tolkien. I had only known those works that were derivatives (or derivatives of derivatives) that had become so self-referential that the original work they were paying homage to or parodying was lost. The work had become about itself and not anything outside of it.

These stories stand out in stark contrast to the later works of fantasy that I’ve read. Modern fantasy and science-fiction authors tend to be fans of fantasy and science fiction themselves. Now, there’s nothing wrong with that – I am a fan of fantasy stories myself! However, when you are mainly familiar with fictional works, your work will have a derivative quality. Your audience will get the impression that they are simply watching the same cliches cynically presented before them. To avoid this, some authors will try and get “clever.” They will try subverting the audience’s expectations. Star Wars’ Rey was just a nobody from an unimportant family – until she wasn’t. This main character may have been summoned to this fantasy world to be its hero, but he’s going to relax and have fun instead. While these subversions can be clever, they can wind up becoming unoriginal.

Older writers of fantasy and science fiction were classically-educated men knowledgeable in history, language, and mythology. This knowledge shaped the worlds they created, breathing life into the imaginary lands and characters. Their deep understanding of the real world made their fantasy worlds more believable, allowing us to become immersed in them. By contrast, people who make modern fantasy books, comics, movies, and video games are not generally knowledgeable about reality thanks to the poorer quality of their education. Rather, they are knowledgeable about popular culture itself. Instead of their work being a derivative of reality, their work is a derivative of a derivative of reality (or a derivative of a derivative of a derivative of a derivative…). It is the world around us that provides the endless material with which the imagination can create new stories.

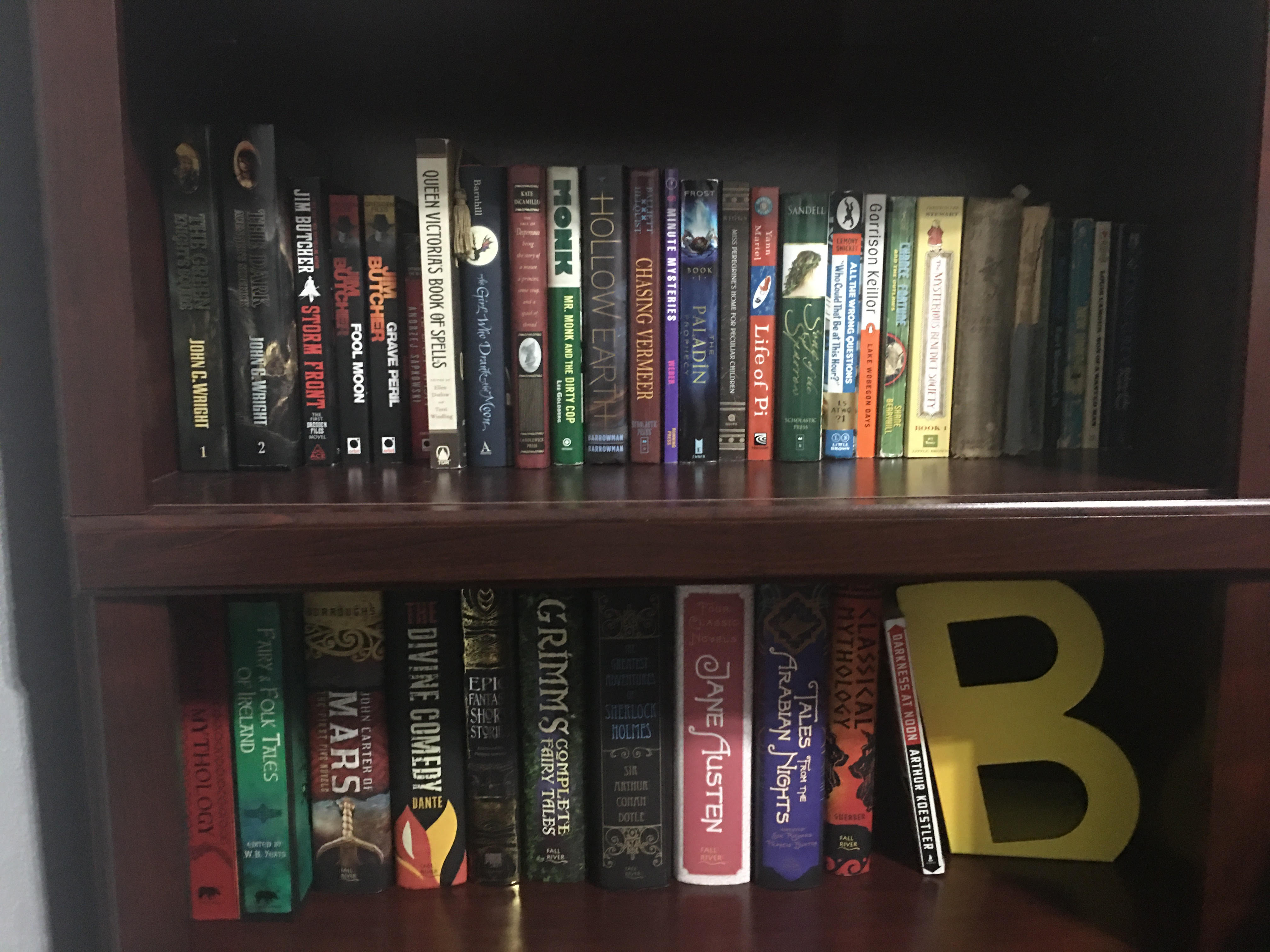

I do not say this to attack these people. Even I am not immune. Though I have an appreciation for the classics, I’ve not read all of them. Though I love history and mythology, I’m not as knowledgeable as I could be. As a result, when I try to come up with fictional ideas, they often come across as inferior fanfiction. Still, I think that we owe it to others to share these older works around. The kinds of things that were written before we were born still hold up to this day, and they can inspire us.

The reason fictional works delight us is that they are imitations of reality. They distill all of the things that make life interesting into one written work. Real-life history and mythology are richer than anything any one person can dream up on his own, so it makes sense that they would be a font of creativity to draw upon. Authors that draw upon derivatives of these things mistake a lesser stream of ideas for their source and end up limiting their creative potential. People who want to get into writing fiction should not neglect history and mythology but should instead embrace it.

Leave a Reply