The first word most people tend to describe academics with is “aloof.” Academics don’t have a reputation for being concerned with the problems of everyday people. Professional academics are more likely to interact with literature created by other academics than they are with someone outside their ivory towers, or so they say. This isn’t true for every brainiac though, especially not for St. Thomas Aquinas.

For the past couple of weeks, I’ve been reading Kevin Vost’s book How to Think Like Aquinas: The Sure Way to Perfect Your Mental Powers, and I have been loving it. I’ll write a post on it once I’m done with the book, but for now, I’ll just say that the advice it gives speaks to me.

One of the things I like about St. Thomas is that, while he was capable of talking about some rather complex and abstract topics, he also had plenty of good advice for the common man as well. Part of this, I think, comes from his Aristotelianism. St. Thomas knew that we are our bodies, not a ghost inside a husk. Taking care of our minds and bodies was of utmost importance to him. Today’s blog focuses on what I believe to be his most helpful treatise: his remedies for sorrow.

St. Thomas’ discussion on sorrow can be found in the Summa Theologiae’s Prima Secundæ Partis questions thirty-five through thirty-nine. Sorrow is, according to St. Thomas, a passion felt by the very soul of a person. Anyone whose heart has been gripped with sorrow knows this well. The object of sorrow – that is, what a sorrowful person generally feels sorry about – is some evil or misfortune that happens to him. Sorrow can be caused by loss you experience or remorse for an evil act you did once, but it always hurts.

St. Thomas identifies four types of sorrow – one sinful type, and three others that aren’t. First, there is “anxiety,” a type of sorrow that “weighs on the mind,” making escape seem impossible. This is the stress caused by feeling trapped in a painful situation.

The second is “torpor.” Like anxiety, torpor weighs on the mind. In this case, it weighs so heavily “that even the limbs become motionless” and the affected are unable to speak. Think of those times when you felt so sad that you lost all motivation to do much of anything.

The third kind is pity, “which is sorrow for another’s evil.” This is a much deeper feeling than merely feeling regret for another’s misfortune or being troubled by it. Rather, the pitier feels the suffering of one he pities as his suffering.

The last type of sorrow is envy, which is the sorrow felt at another’s good out of a sense of self-worth. The envious person sees the excellence of another as an affront to his dignity and thus experiences another’s good as his evil. Envy is different from the other types of sorrow in that it is always wrong. While the other types of sorrow can lead to sin if taken too far, envy is never okay. Envy can only be countered by learning to celebrate others’ accomplishments and strive to imitate their good example. Once we do that, the source of our envy will disappear.

For other forms of sorrow, St. Thomas gives the following five remedies.

- Pleasure

According to Aquinas, pleasure arises from obtaining some good, which makes it the opposite of sorrow, which is caused by some evil. Aquinas compares using pleasure to calm sorrow to sitting down to rest after doing hard, physical labor. Pleasure is the soul’s form of resting after spending so long desiring something good. This makes it opposed to sorrow, which is caused by the soul being led into something undesirable. Therefore, laughter, good company, and wholesome entertainment allow weary minds to put down their burdens and enjoy life.

- Weeping

As counterintuitive as it might seem, weeping – real, honest-to-goodness crying – can ultimately lift the spirits. By releasing the sorrow in one’s soul through tears, groaning, or even words, one’s inward sorrow is lessened. If “a hurtful thing hurts yet more if we keep it shut up,” St. Thomas advises, then it’s best that it “be allowed to escape.” He also says that it feels more pleasant to act how one feels, so if a sorrowful person weeps, it will be pleasant to him, and pleasure eases sorrow, as stated above.

- The sympathy of friends

There’s an old saying that “misery loves company,” and, in a way, St. Thomas would agree. Since sorrow is like a physical burden, sharing it will naturally lessen its weight. Also, seeing the love of a friend is always pleasing, and consolation is one way of showing one’s love. This creates pleasure that, again, will ease sorrow. That said, making someone else feel miserable when you’re miserable is not a good way to make you feel less sorrowful, as it would only weigh down the conscience.

- Contemplating the truth

Thomas Aquinas defended the contemplative life – that is, the life of the philosopher, the monk, and the truth-seeker – as the highest form of pleasure possible to mankind on the basis that the intellect was our highest faculty as humans since it is through it that we know God. Since it is the highest form of pleasure, it is, logically, one of the best antidotes to sorrow. Thinking about God’s goodness and the prospect of eternal beatitude can chase away any sadness, of course. But the sheer act of thinking about higher things can carry your mind away from those things that weigh it down.

- Sleep and baths

Because sorrow is, by its nature, “repugnant to the vital movement of the body,” anything that “restores the bodily nature to its due state of vital movement, is opposed to sorrow and assuages it.” Because the body and its soul are intimately linked to each other, caring for the body can soothe both body and soul. For this, the Angelic Doctor prescribes a nice, warm bath, a nap, or else something else to soothingly care for the body.

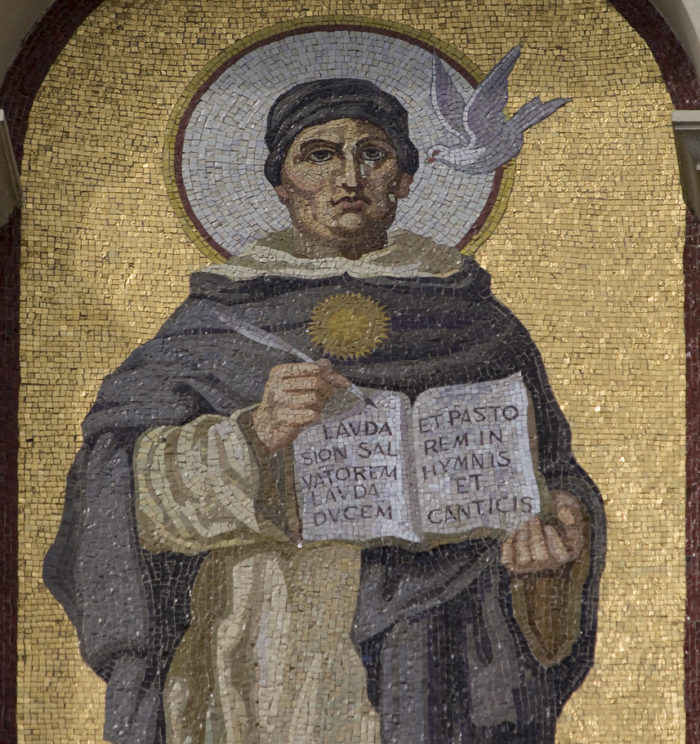

In any case, I thought I should share with you some interesting nuggets of wisdom from one of Catholicism’s greatest theologians. It’s interesting how much of this advice comes across as the kinds of folk wisdom that could’ve easily come from my grandparents, yet it’s expressed in the technical and precise language of a philosopher. The contrast is bizarre yet fitting because, again, St. Thomas’s concerns were very much grounded in the actual good of actual people. For this reason, and many others, I do love the Patron Saint of Scholars.

whoah this weblog is wonderful i like studying your posts.

Stay up the great work! You realize, a lot of individuals are

searching round for this info, you could help them greatly.

Hello everyone, it’s my first visit at this site, and article is genuinely fruitful in favor of me,

keep up posting these posts.

It’s impressive that you are getting ideas from this article as well

as from our argument made at this place.