Have you ever seen an online post that was so wrong that it makes you feel like you have to respond to it? I’m sure you’ve had that urge if you’ve been on social media long enough. While I don’t have a social media account, I do subscribe to a few newsletters created by authors. I follow them for the advice they give on writing, making money, and life in general. One of them being the newsletter of Bob Bly (Click here to check out his website).

In his newsletter, Mr. Bly gives suggestions on how to be a better copywriter and person. His newsletters are generally short, witty, and full of sage advice. But sometimes, he gets things wrong. In a post entitled “Is it possible you could be wrong about global warming?”, he argues against Mr. Schapiro, an “articulate and intellectual pundit.” Mr. Schapiro claims that having the credentials doesn’t make you correct. That is determined by the rightness of the argument. In response to this, Mr. Bly replies:

Well, this may hold true in fields that are not especially expert. But I contend in fields that are expert, Schapiro’s thesis is not as strong.

For instance, you may strongly believe that climate change is a hoax — although weather patterns and rising sea levels seem to say otherwise.

The anti-climate change believer will Google article after article in which scientists say yes, global warming is baloney.

You can find an equal number of articles in which other scientists warn that global warming is very real.

The problem is this: most of us do not have the STEM education to evaluate the science behind either argument.

And climate IS an especially expert field. So their opinion, as climatologists, is stronger than arguments expressed by art history majors.

When a layman says “I have read a lot about it,” I applaud his interest — but most don’t have the necessary background to interpret, much less understand, the data they are looking at.

Conclusion: If people would limit themselves to expressing opinions on things they actually understand and know something about, contentious arguments degrading to personal insults would decline an order of magnitude.

In other words, they would shut their pie holes.

Now, there is a grain of truth in this: people who open their mouths and confidently say things when they don’t know what they’re talking about are foolish. Experts do exist for a reason – it is their job to “study the data” while you are living your normal life. They are a useful shorthand for people who aren’t paying attention to the issues. However, Mr. Bly’s argument lacks nuance, to put it mildly.

My first point of contention is this: what is this “background” that gives experts their credibility? Besides a fancy piece of paper, what separates “experts” from well-educated laymen? Mr. Bly’s argument seems to be that the mere fact that they are experts is what qualifies them. They went to school and got a neat certificate, so they must know more than you. But this doesn’t inspire confidence at all.

In the first place, we know throughout history that serious scientific discoveries that turned out to have been true were rejected and even ridiculed by the experts of their time. The “experts” at different points in time mocked the germ theory of diseases, the existence of meteorites, the idea of plate tectonics, the theory that rockets could break from Earth’s atmosphere, and many other ideas that came in time to have widespread acceptance. Some of these ideas came to be accepted by a consensus of experts only a few years after those very same experts blackballed the theorists that came up with the ideas.

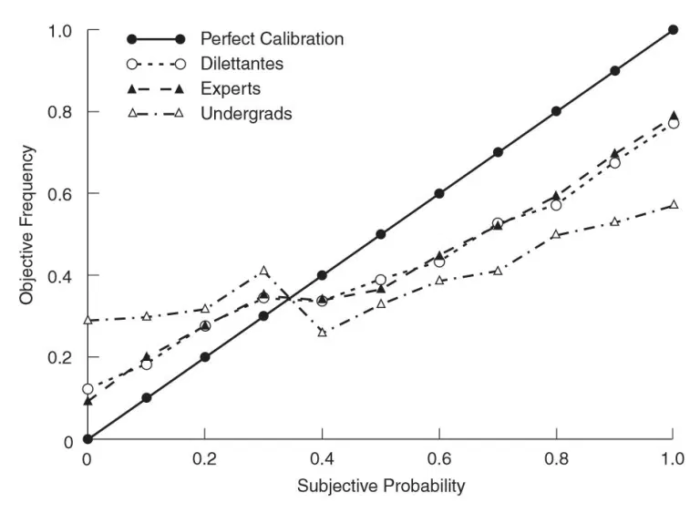

For what it’s worth, the scientific data seems to back this up. Tetlock (2004) had a sample of 284 experts make 27,451 predictions in various fields between 1988 and 2003. Professor Tetlock found that experts were on par with dilettantes and only a bit better than undergraduate students at making predictions.

Not only are these academic experts bad at predicting the future based on the data they’ve collected, they often don’t know how to read that data. A wide number of studies (like Lyu et al. (2019), Lecoutre et al. (2003), and Zuckerman et al. (1993)) show that academic experts (including statisticians) are too statistically illiterate to responsibly conduct empirical research.

Here, it’s important to distinguish between the three parts of a scientific study. There’s “raw data,” there’s the “interpretation of raw data,” and there’s the “application of data.” Raw data is what is meant when one asks for “just the facts, ma’am.” It is the raw statistics that professional scientists produce using their experiments and devices. To take Mr. Bly’s example, various temperature and air pressure measurements climatologists make are examples of raw data.

The interpretation of the raw data contextualizes the data by forming a story. It’s all well and good if you can get a bunch of raw data, but what does it all mean in the end? How does it all logically cohere with itself and the wider world? For instance, climatologists can then use the data to talk about how their measurements show that the Earth is heating up over time.

Finally, the application of data is how we derive consequences from the data and apply it to new circumstances. These would be the kind of predictions and policy proposals that climate change experts derive from their interpretation of the data, like the idea that global warming is an imminent threat to humanity.

As the above shows, academic experts are not good at interpreting or applying the data they produce in their experiments, at least not better than educated laymen are. This does not mean that academic experts are the most unreliable source of information or that we ought to dismiss what they say. But what this does mean is that we shouldn’t let these experts do our reasoning for us. Mr. Bly’s blithe dismissal of well-read laymen can only be the result of prejudice.

And this isn’t even getting into the idea that the experts might not be trustworthy. How do we know that these technical experts aren’t making things up? Lying for the sake of expediency, careerism, or political gain happens more often than not. For example, Dr. Anthony Fauci last year admitted that he and other officials lied to the public when they claimed that face masks were unnecessary. This is no mere anecdote either. A surprising number of scientists commit fraud and malpractice, as seen in this study.

I love experts as much as the next guy, but there’s a certain amount of thinking one must do for oneself. There is such a thing as common sense, after all. Finding a balance between expert opinion and common sense is necessary to navigate a world full of misinformation, bias, and ignorance. Those who argue that we ought to “trust the experts” because they have the right “background” ought to ask themselves why they think a piece of paper proves that someone can be trusted. If they did, they’d find themselves a little wiser for it.

Leave a Reply